Just a kid

I’m standing on a wooden deck behind a tepee in the middle of the desert. It’s 1996 and it’s got to be at least 110 degrees. This little kid named Ricky has just asked me where I’m from. I say Seattle and just behind me I hear another kid say “boom!” I look over my shoulder but I can’t tell who said it. I turn back to Ricky and he asks me where I’m from again like he didn’t hear me the first time. I say Seattle again. I hear from behind me, “boom!” I must look confused because another kid looks at me and says, “He blew up Seattle.” I just laugh. “No man, he blew it up, like dissed your home town.” He’s dead serious. Now I’m laughing even harder.

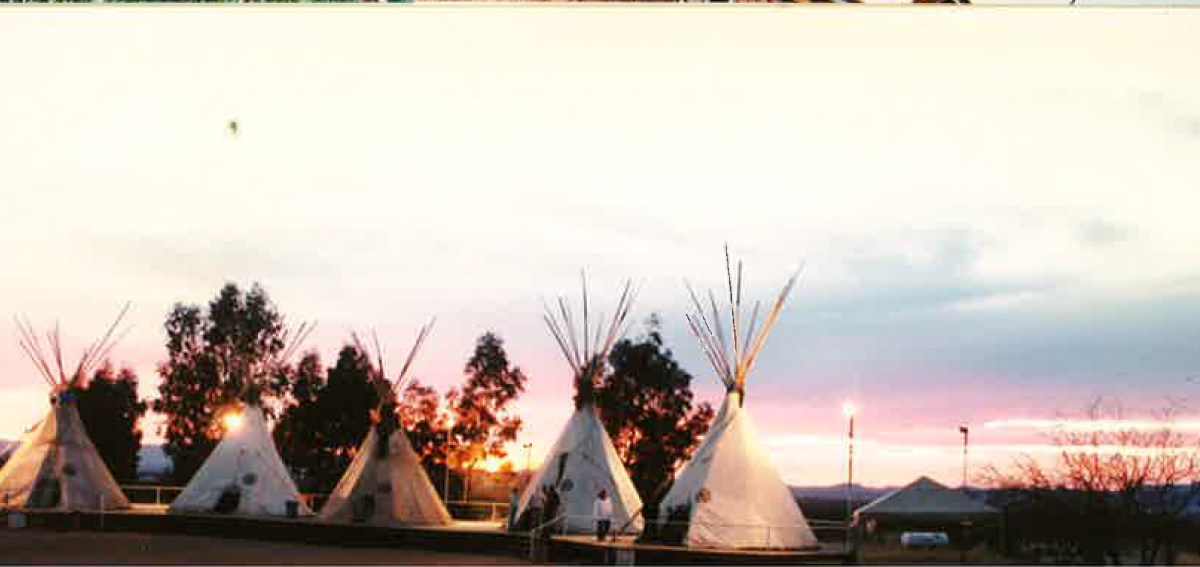

It’s my first day as a “tepee parent” at a wilderness camp for adjudicated youth. What that means is that I’m in the desert an hour and a half southeast of Tucson, Arizona in charge of a group of kids sent to the desert by the courts. The kids are from all over; Tucson, Los Angeles, the San Joaquin Valley, Chicago, Philly, and New Jersey. None of them want to be there and their one goal for this particular day is to see what the new guy is made of. I’ve just gotten out of a week of orientation and this is my first time alone with the kids. I’m not sure what to expect from them and they don’t know what to expect from me. What I begin to understand is that not knowing what to expect is not a safe condition. The kids need to know that they are safe and if they don’t know what to expect from me they don’t feel safe. So they test.

In the next few days, I start to get my bearings and I decide that of the 70 or so kids in the camp, most of them are just kids that have made some bad choices. But I also feel that there is a group that has done more than make bad choices. A group that has not only made bad choices but done bad things. A group of kids that might actually be dangerous. One of these kids is a big, handsome, 17 year old named Richard. That first day he doesn’t “blow up” Seattle, he doesn’t laugh with the other kids when they make fun of my “skinny jeans”, and he doesn’t ask questions. He just watches.

Sometime later, at lunch, as we walk into the cafeteria I see Richard watching me again. He’s sitting at the second table in. Just apart from most of the other kids. Both hands are balled up on the table in front of him. His chin is tilted toward his chest. His huge dark eyes are fixed on me. I can only see half of the brown in his eyes, the rest is the whites. He doesn’t blink. He just watches me. I think to myself, “this kid wants to kill me.” And I believe it.

During orientation, we’d been warned that the kids were going to test us. That it would be in little things like “boom” all the way to physical testing. I had my share of both. It felt like Richard was testing me in a different way. Like he was looking inside me to see if I was worth letting survive here. In the first week, he never spoke to me but he got into my head. I found myself avoiding him, making sure that I wasn’t running his group or checking the bathroom when he was in there. I made sure that we were never alone together. To be perfectly honest, I was scared of the kid.

I’m not a big guy. I come from a small town. I’ve got very little in common with these kids. I can’t relate to them directly. But I’ve got two things going for me. I’m consistent and I don’t get mad. No matter how charged situations get, I keep my cool. Because of this, the kids start to know what to expect from me. They start to understand that I’m safe. They figure out that I keep the boundaries, that I’ll call them on their shit, that I’ll raise my voice when it needs to happen, and that I’ll put them on the ground if it comes to it. What they also understand is that I’ll do it without anger, that they’ll be safe the whole time. It’s because of this understanding that I start to make relationships with kids in the camp.

As the kids start to feel safe with me I start to feel safe with them. Safe enough to let down my guard with Richard from time to time. I figured that if he was going to do something to me he probably would have done it by now. He was still an enigma to me. Never opening up in group, never really talking with any of the other kids, not part of any of the crews in the camp. He’d play basketball sometimes and he seemed to enjoy working with the horses. I was less scared of him than I’d been at the beginning and because of that, late one night, he got me alone.

It was after lights out and I had another kid sitting with me outside the tepee away from the platform. It wasn’t particularly late, the sun still giving some color to the horizon, but most of the camp was in their bags. I was up with this kid because he’d had a bad phone call that day and needed to process it before he thought he could sleep. The fact that he asked me to spend some time with him talking about it instead of just blowing up on someone was progress so I felt good taking some extra time with him. As we were talking he suddenly stopped, looked up, and nodded. I followed his eyes down and into the shadows to our right and saw Richard looking up at us. The kid I had been talking to stood up and walked away. He didn’t say anything and he didn’t look back.

Richard waited a beat then started toward me. I decided that the best thing for me to do was to sit still and play it out. One way or another we’d get this out of the way. He walked up the stairs I was sitting on and sat down next to me. For the next 10 seconds or so we both just looked out over the desert, not saying a word. I willed myself to stay calm. Maybe he just wanted to fuck with me. Just more intimidation. We both just sat there with our forearms on our knees, looking straight ahead. Richard broke the silence.

“Yo man, how you do it?” He asked, still not looking at me.

“Do what?” I asked.

“Keep from getting mad. How do you do it? I see you man… people be making fun of you, throwing shit at you, calling you names, you never get mad. How do you do it?” He finally looked at me.

I thought about it for a minute. I wasn’t sure that I knew the answer. Finally, I said, “getting mad doesn’t help.”

“I get that. But how do you control it? How do you let people play you like that and keep your shit?”

I knew that I didn’t have a great answer for this one. I really didn’t know. But he wasn’t looking for an answer at this point. He just wanted to talk.

“I got a kid. A daughter. She’s only 18 months old. And I’m here. I’m here and she’s back in the valley with her moms. I’m stuck in this shit-hole for 9 more months if I’m lucky and I’m mad all the time man. All the time. I don’t know what to do.” He was crying now.

I put my arm around his shoulders and he sank into my side shaking with sobs. Just a kid that had made some bad choices after all.

I worked with Richard quite a bit in the next 9 months. We worked on all kinds of things that he’d need to figure out before he went back home to his daughter. We worked on his resume, we tried to get him into the army, we did interview training, and we worked on his anger. When he left he gave me a real hug and thanked me. He felt as ready as he was going to be. I agreed.

I’ve been out of that camp for more than 20 years now. Every once in a while I try to look up one of the kids that I worked with. I don’t always remember their names and I don’t find info on many of them. A couple of years ago I looked up Richard. What I found gutted me.

STOCKTON – A Stockton man was sentenced Monday to life in prison for murdering an 18-year-old mother, and the judge piled on more time for the killer’s fleeting escape last year from the Courthouse in downtown Stockton.

When you work with kids you work with the idea that if you can help just one then it will all be worth it. But you want to think that maybe you helped them all in some way. I don’t know if I helped Richard or not. I don’t pretend to know what happened to Richard after he left the camp. I don’t know what I expected Richard to go on to do. I’m not going to try to say that I really knew Richard. The situation in which we found ourselves together was not reality. It had none of the stresses that come from real life. What I know is that we worked hard to help give Richard a second chance. He was worth that second chance, I just wish he’d used it.